Dear Senator Byrd

By Lewis F. McIntyre

FrontPageMagazine.com | February 13, 2004

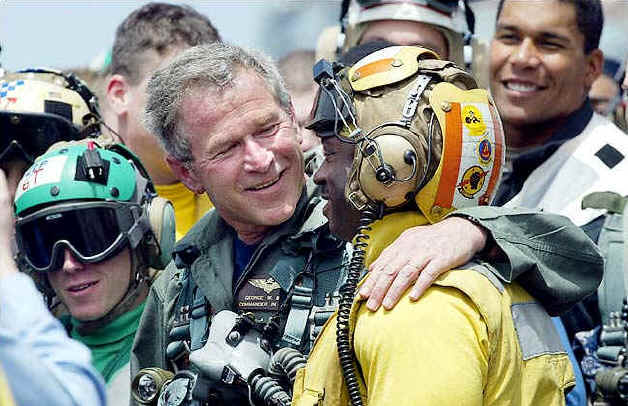

Below is USN (Ret) CDR Lewis F. McIntyre's letter to Senator Byrd about President Bush's visit to the USS Abraham

Lincoln (photos added later).

Senator Byrd,

As a retired Naval Officer, with two Gulf carrier deployments under my belt, I find your criticism of President Bush's visit to the Lincoln offensive in the extreme! This is the first time that the Commander-in-Chief took time out of his schedule to pay a visit to thank those who served in the line of fire, in a way that was both dramatic and meaningful to those on the carrier.

Perhaps if LBJ got off his fat ass to do something similar, our troops' morale in Vietnam might not have been so low.

As a Naval officer, I am extremely sensitive to styles of leadership.

That is, after all, our stock in trade. And it was not lost on me that the President spent about thirty seconds shaking hands with the Admiral, CO, and CAG (If you don't know these abbreviations just look them up in your Funk &

Wagnalls!) He then spent the next forty-five minutes putting himself at the disposal of the people who make that ship work, the yellow shirts, the green shirts,

the purple shirts, the chiefs, the sailors.

If you don't know the significance of those colored shirts, look it up in your Blue Jacket's Manual. Not dressed out in formal uniform (I understand at Bush's request), but in their greasy, smelly, sweaty working uniforms ... working a flight deck is hot, hard work. And yet he, in his flight suit, put himself at their disposal, this was their moment for 19 or 20 something year old kids a few years out of high school, to get a picture of themselves with the President of the United States, his arm draped around their shoulder.

That is a moment that those kids never dreamed would ever happen to them, maybe not even when they knew he was coming aboard. Surely, he would see the brass, not the troops. But it was the troops to whom he gave his time ... and it was the most natural moment in the world. You might have thought it was a family reunion, and in a way, it was...

Bush is one of them, the common man, and while he is still the most powerful man on the planet right now. He hasn't lost his touch for them.

Was it a political moment?

What moment of a president's life is NOT a political moment? Was it grand standing, to come in to an OK pass to a 4 wire, a bit high in close, correcting, left of centerline? Well, hell, he didn't fly the approach anyway, though I understand from the pilots who flew him that he did a pretty good job at formation flying, tucked in close for a lead change. You can always tell a fighter pilot, you just can't tell him very much. And, apparently after thirty years, it all comes back, with a little coaching, I am sure. Frankly, I would have liked to see him come aboard in an FA-18, but the Secret Service vetoed that, and Bush accepted their judgment ... again, a mark of a good leader.

If you had spent some time in the service, instead of the Klan, you might understand the significance of that moment to all the men and women aboard the Lincoln, and indeed to all the men and women in the service who shared that moment vicariously. But you chose the bedsheet instead of the uniform, and so you don't.

I am half-tempted to move to West Virginia just so I could vote against you in your next election.

Lewis F. McIntyre

CDR, USN (Ret)

Over Najaf, Fighting for Des Moines

August 23, 2004

OP-ED CONTRIBUTOR

By GLEN G. BUTLER

Najaf, Iraq -- I'm an average American who grew up watching "Brady Bunch" reruns, playing dodge ball and listening to Van Halen. I love the Longhorns

and the Eagles. I'm you; your neighbor; the kid you used to go sledding with but who took a different career path in college. Now, I'm a Marine

helicopter pilot who has spent the last two weeks heavily engaged with enemy forces here. I'm writing this between missions, without much time or care to

polish, so please look to the heart of these thoughts and not their structure.

I got in country a little more than a month ago, eager to do my part here for the global war on terror and still get home in one piece. I'm a

mid-grade officer, so I probably have a better-than-average understanding of the complexity of the situation, but I make no claims to see the bigger

picture or offer any strategic solutions. Two years of my military training were spent in Quantico, Va., classrooms. I've read Sun Tzu several times;

I've flipped through Mao's Little Red Book and debated over Thucydides; I've analyzed Henry Kissinger's "Diplomacy" and Clausewitz's "On War"; and I've

walked the battlefields of Antietam, Belleau Wood, Majuba and Isandlwana.

I've also studied a little about the culture I'm deep in the middle of, know a bit about the caliph, about the five pillars and about Allah, but know I

don't know enough. I am also a believer in our cause - I put that up front just so there isn't any question of my motivation.

We marines are proudly apolitical, yet stereotypically right-wing conservative. I'm both. And I'd be here with my fellow

devildogs, fighting just as hard, whether John Kerry or George W. Bush or Ralph Nader were our

commander-in-chief, until we're told to go home.

The other day I attended a memorial service for an old acquaintance, Lt. Col. David (Rhino) Greene. He was killed July 28 while flying his AH-1W

Cobra over the eastern edge of Ramadi. His squadron was composed of reservists: "old guys" like me who had been around a little while. But

unlike me, these guys had gotten out of active duty to pursue other careers and spend more time with their families. Now, they were leading the charge

against the Iraqi insurgency.

The night after the service, I sat around in an impromptu gathering of $10 beach chairs in the sand, watching the sunset and smoking some of Rhino's

cigars with friends I hadn't seen in almost a decade. I listened in awe as they told me about their Falluja April, about how they had all cheated

death, been shot down, again and again. We talked about the war, pretending to know all the answers, and we traded stories about home, bragged about our

wives and kids.

We also talked about the magic bullet that ended Rhino's life. It could have been shot by a sniper who had slipped in over the Iranian border, or maybe

it came from the AK-47 of a rebellious Iraqi teenager who viewed shooting at Yankee helicopters the same way mischievous American kids might view

throwing rocks at cars. No matter, the single round pierced his neck, and within seconds a good man was dead, leaving his wife a widow and his two

children fatherless. I won't soon forget that day, but it was quickly overshadowed by events to come, as I was thrust into the heat of battle in

my own little slice of Mesopotamia.

On Aug. 5, after a few days of building intensity, war erupted in Najaf (again). When we had first come to Iraq, we were told our mission would be

to conduct so-called SASO, or Security and Stability Operations, and to train the Iraqi military and police to do their jobs so we could go home.

Obviously, the security part of SASO is still the emphasis, but our unit's area of operations had been very quiet for months, so most of us weren't

expecting a fight so soon.

That changed rapidly when marines responded to requests for assistance from the Iraqi forces in Najaf battling Moktada al-Sadr's militia, who had

attacked local police stations. Our helicopters were called on the scene to provide close air support, and soon one of them was shot down. That was when

this war became real for me.

Since then my squadron has been providing continuous support for our engaged Marine brothers on the ground, by this point slugging it out hand-to-hand in

the city's ancient Muslim cemetery. The Imam Ali shrine in Najaf is the burial place of the prophet Muhammad's son-in-law, and is one of the most

revered sites in Shiite Islam. The cemetery to its north is gigantic, filled with New Orleans-style crypts and mausoleums. We had been warned it was an

"exclusion zone" when we got here, that the local authorities had asked us to not go in there or fly overhead, even though we knew the bad guys were

using this area to hide weapons, make improvised explosive devices, and plan against us. Being the culturally sensitive force we are, we agreed - until

Aug. 5. Suddenly, I was conducting support missions over the marines' heads in the graveyard, dodging anti-aircraft artillery and rocket-propelled

grenades and preparing to be shot down, too. My perspective broadened rapidly.

At first there were no news media in Najaf; now, I assume, it's getting crowded, although the authorities have restricted access after a group of

journalists "embedded" with the Mahdi Militia muddied the problem and jeopardized others' safety. I haven't had time to catch much CNN or Fox

News, and although I've seen a few headlines forwarded to me by friends, I don't think the world is seeing the complete picture.

I want to emphasize that our military is using every means possible to minimize damage to historical, religious and civilian structures, and is

going out of its way to protect the innocent. I have not shot one round without good cause, whether it be in response to machine gun fire aimed at

me or mortars shot at soldiers and marines on the ground.

The battle has been surreal, focused largely in the cemetery, where families continue burying their dead even as I swoop in low overhead to make sure

they aren't sneaking in behind our forces' flanks, or pulling a surface-to-air missile out of the coffin. Children continue playing soccer

in the dirt fields next door, and locals wave to us as we fly over their rooftops in preparation for gun runs into the enemy's positions.

Sure, some of those people might be waving just to make sure we don't shoot them, but I think the majority are on our side. I've learned that this enemy

is not just a mass of angry Iraqis who want us to leave their country, as some would have you believe. The forces we're fighting around Iraq are a

conglomeration of renegade Shiites, former Baathists, Iranians, Syrians, terrorists with ties to Ansar al-Islam and Al Qaeda, petty criminals,

destitute citizens looking for excitement or money, and yes, even a few frustrated Iraqis who worry about Wal-Mart culture infringing on their

neighborhood.

But I see the others who are on our side, appreciate us risking our lives, and know we're in the right. The Iraqi soldiers who are fighting alongside

us are motivated to take their country back. I've not been deluded into thinking that we came here to free the Iraqis. That is indeed the icing on

the cake, but I came here to prevent the still active "grave and gathering threat" from congealing into something we wouldn't be able to stop.

Weapons of mass destruction or no, I'm glad that we ended the dictatorship of Saddam Hussein. My brother and other American jet pilots risked their

lives for years patrolling the "no fly zone" (and occasionally making page A-12 in the newspaper if they dropped a bomb on a threatening missile

battery). The former dictator's attempt to assassinate George H. W. Bush, use of chemical weapons on his own people, and invasion of a neighboring

country are just a few of the other reasons I believe we should have acted sooner. He eventually would have had the means to cause America great harm -

no doubt in my mind.

The pre-emptive doctrine of the current administration will continue to be debated long after I'm gone, but one fact stands for itself: America has not

been hit with another catastrophic attack since 9/11. I firmly believe that our actions in Afghanistan and Iraq are major reasons that we've had it so

good at home. Building a "fortress America" is not only impractical, it's impossible. Prudent homeland security measures are vital, to be sure, but

attacking the source of the threat remains essential.

Now we are on the verge of victory or defeat in Iraq. Success depends not only on battlefield superiority, but also on the trust and confidence of the

American people. I've read some articles recently that call for cutting back our military presence in Iraq and moving our troops to the peripheries of

most cities. Such advice is well-intentioned but wrong - it would soon lead to a total withdrawal. Our goal needs to be a safe Iraq, free of militias

and terrorists; if we simply pull back and run, then the region will pose an even greater threat than it did before the invasion. I also fear if we do

not win this battle here and now, my 7-year-old son might find himself here in 10 or 11 years, fighting the same enemies and their sons.

When critics of the war say their advocacy is on behalf of those of us risking our lives here, it's a type of false patriotism. I believe that when

Americans say they "support our troops," it should include supporting our mission, not just sending us care packages. They don't have to believe in

the cause as I do; but they should not denigrate it. That only aids the enemy in defeating us strategically.

Michael Moore recently asked Bill O'Reilly if he would sacrifice his son for

Falluja. A clever rhetorical device, but it's the wrong question: this war is about Des Moines, not Falluja. This country is breeding and attracting

militants who are all eager to grab box cutters, dirty bombs, suicide vests or biological weapons, and then come fight us in Chicago, Santa Monica or

Long Island. Falluja, in fact, was very close to becoming a city our forces could have controlled, and then given new schools and sewers and hospitals,

before we pulled back in the spring. Now, essentially ignored, it has become a

Taliban-like state of Islamic extremism, a terrorist safe haven. We must not let the same fate befall Najaf or Ramadi or the rest of Iraq.

No, I would not sacrifice myself, my parents would not sacrifice me, and President Bush would not sacrifice a single marine or soldier simply for

Falluja. Rather, that symbolic city is but one step toward a free and democratic Iraq, which is one step closer to a more safe and secure America.

I miss my family, my friends and my country, but right now there is nowhere else I'd rather be. I am a United States Marine.

Glen G. Butler is a major in the Marines.

A Chaplain's Unger's perspective on activities in IRAQ

Chaplain Unger is from MCCDC Doctrine Division. He's been in Iraq for the

past four months.

30 May 2004

Dear Friends,

This is my third letter from Iraq. I have been working myself into the

right mood to do this. Today is the day. In my last two letters I have leaned toward being as upbeat as possible. This time will be different;

today I want to talk about Memorial Day, but I will start off by giving my perspective on the Abu Ghraib prison problem.

First off, the investigation into the abuses at Abu Ghraib began back in January. That is why the first court martial was ready for

trial in May. The senior people here knew about the investigation; the rest of us didn't. By the time the media "broke" the story, the

investigation was almost done and the soldiers who had committed the abuses had already been rotated home.

Second, I (we) don't see all the news coverage that you in the states see.

I do see some Fox News and CNN. Fox editorializes toward the right wing; CNN is the voice of the anti-war movement. I wonder that if CNN had been

around in 1942 we might all be speaking German and Japanese. I can tell you this, everything I have heard on CNN is so biased, negative, and

out-of-touch that I will never watch CNN for the rest of my life. That being said, when the rest of us found out about the abuses we were shocked

and sickened. I think maybe more so than people back home because we are here; these are the people I see every day. The people I see every day

who are going out to fix: schools, hospitals, reservoirs, power plants, and sewer systems. They do these things risking sniper fire and hidden

explosives. These soldiers are not a handful of bad apples like those at Abu

Ghraib, these soldiers number into the thousands. Now think for a second, how much have you seen about that on the news? I believe Abu

Ghraib should have been reported, but when I see the fixation of the media on the actions of a few, when the courage shown in reconstruction and the

restraint shown in combat by thousands of our people is never shown, I believe this is inexcusable. For the real story of what our people are

doing here, go to www.cjtf7.com/index.htm. Click on Coalition News and then Humanitarian Efforts.

Third, what happened on that cellblock of Abu Ghraib is what happens when

leadership is not out walking around. That is true in the military or in college dorms. I haven't seen it reported in the news, but other soldiers

turned in the soldiers who did this. If the dirt bags that committed those abuses had been turned loose among the troops here it would've been ugly.

I haven't heard any comments about them coming from soldiers that didn't express a hope that they would get the maximum punishment. A few leaders

need to get demoted too.

As per the "outrage", if you were "outraged" by this, good. I was.

However, I would like to ask Arab governments and our own media elites, "Were you just as outraged by what happened under Saddam? If so, you

didn't show it."

Here is what people need to understand: the interrogation of prisoners of

war is a little tougher than what the typical thug gets by the local police. I went to Survival, Evasion, Rescue, and Escape (SERE) School back

in 1995. I am more proud of completing that course than anything I have ever done. Also, I would never do it again. After playing hide and seek

with "bad guys" in California in March, we all got caught, knocked around, froze, went hungry, sleep deprived, threatened with worse, and then

interrogated. Here's the deal: when interrogation is done correctly, people don't break so much as they leak. (The purpose of SERE is to teach

you how not to leak. That is the classified part of the school.) The interrogator wants them to leak in a way so that the prisoner doesn't even

know he is leaking. When someone breaks, as opposed to leaking, they usually give out a data dump of gibberish and then physiologically shuts

down. A good interrogator avoids that. If you hurt them or scare them too badly, they quit leaking. Interrogators ask the same question about ten

times, ten different ways. Disoriented people leak and they don't even know it. What most Americans think of when they think of POWs being

interrogated is what they remember of our pilots in North Vietnam. The abuse our people went through in Vietnam wasn't to get intelligence; it was

to exploit them for propaganda purposes. I mention this to put the term "abuse" in context. When a terrorist here in Iraq or jaywalkers back in

the states report jailhouse "abuse," what does it mean? When we catch a guy red-handed restocking his weapons stock and question him, withholding

his TV privileges isn't enough. He won't be happy, but neither will he be destroyed or scared for life. He will tell his buddies, "I didn't tell

them anything." In fact he will have told us a lot.

As I said, I had to work myself into a mindset to talk about this. To work

around horror without out letting the horror seep into your soul is a spiritual battle. This week I worked with a National Guard soldier who had

to clean up after a convoy of civilian aid workers were killed when an Improvised Explosive Device (IED) went off on the road into Baghdad. He is

a carpenter in civilian life, but this week he was out on a highway picking up arms and legs while watching out for snipers. He was cleaning up after

monsters. Some other young Americans were put in charge of guarding monsters and then became monsters. Care of the soul is serious business.

That is part of the reason why I became a Navy Chaplain.

The other reason is the people. The folks I have known in the military are

more interesting to be around than anybody else I know. This leads me to Memorial Day. Earlier this month I went to Camp Cooke at Taji. (To lend

perspective, Taji is really north Baghdad; I am in west Baghdad.) The 39th Brigade (Arkansas National Guard) is stationed there. I didn't know any of

them, but I wanted to see my home-state Guard here in Iraq. So I badgered my way into flying up there for two days. They are stationed in the old

Iraqi army air defense school. Unlike downtown Baghdad, the old air defense school was turned into rubble. It is getting better, but it was

like living in a junkyard.

Their first month in Iraq was tough. These soldiers patrol the roughest part of Baghdad. While I was there, the Chaplain of the 39th told me this

story: One of the old troopers who came was a 52 year-old Sgt. who had already done his 20+ years and had retired. But his son was in the 39th,

and when the father found out they were coming over here, he reenlisted. On their first week in country, Camp Cooke was attacked by rockets and the

first rocket that landed killed the father.

I was born in 1958 and came of age when the Vietnam War and the anti-war

movement were both in full swing. It has taken me years to put this into words, but I believe that as bad as that war was, the legacy of the

anti-war movement was worse. The anti-war movement gave rise to the moral superiority of non-involvement and non-commitment. While that may have

worked to help draft-dodgers sleep at night, it's not much of a strategy of how to go through life. Taken to its logical conclusion the message is:

don't commit to your county, don't commit to your spouse, and don't commit to your kids, church, or community. Don't commit to cleaning up your own

mess or any cause that demands any more from you than rhetoric. This was the mindset in which our country was firmly stuck. Until 9/11,

some woke up. Kids came down and joined the service. To the dismay of some of their teachers, parents, and the media elites, they came down here

and raised their hand in front of the flag. And they are still coming to the shock of the non-committers. The Marines have more enlisting than

their two boot camps can handle.

And we are all here together for Memorial Day 2004. Old National

Guardsmen, grandfathers, and single moms, Texans and Mexicans, Surfers and Rednecks. A few weeks ago an Illinois National Guardsman, mother of

three, was hit six times, saved by her body armor, but lost part of her nose. She stayed on her 50 caliber, firing on the bad guys, protecting the

convoy. She said she was thinking of her kids and the guys she was with. Commitment is love acted out. It is sad that the non-committers missed

that. They and their moral high-ground haven't been near a mass grave. The kids I see and eat with every day still want to help this country, in spite

of getting shot at while doing it. That is love acted out. You either get it, or you don't.

During my time in Iraq I won't be able to see any of the Biblical sites

that are here. But a few weeks ago in Taji I got to stand on some holy ground, where a father died when he went to war just to be with his son.

Sincerely yours,

Steven P. Unger

LCDR, CHC, USN

Multi National Corps-Iraq

Its the Very First Day of the War

An Elite Athlete

By Tom Demerly

It is dark and Mike Smith's clothing is wet. Mike Smith is an athlete, an elite athlete in fact. He is a triathlete, has done Ironman several times, a couple adventure races and even run the Marathon Des Sables in Morocco- a 152 mile running race through the Sahara, done in stages.

Mike has some college, is gifted in foreign languages, reads a lot and has an amazing memory for details. He enjoys travel. He is a quiet guy but a very good athlete. Mike's friends say he has a natural toughness. He can't spend as much time training for triathlons as he'd like to because his job keeps him busy. Especially now. This is Mike's busy season. But he still seems very fit. Even without much training Mike has managed some impressive performances in endurance events.

It's a big night for Mike. He's at work tonight. As I mentioned his clothing is wet, partially from dew, partially from perspiration. He and his four co-workers, Dan, Larry, Pete and Maurice are working on a rooftop at the corner of Jamia St. and Khulafa St. across from Omar Bin Yasir. Mike is looking through the viewfinder of a British made Pilkington LF25 laser designator. The crosshairs are centered on a ventilation shaft. The shaft is on the roof of The Republican Guard Palace in downtown Baghdad across the Tigris River.

It's a big night for Mike. He's at work tonight. As I mentioned his clothing is wet, partially from dew, partially from perspiration. He and his four co-workers, Dan, Larry, Pete and Maurice are working on a rooftop at the corner of Jamia St. and Khulafa St. across from Omar Bin Yasir. Mike is looking through the viewfinder of a British made Pilkington LF25 laser designator. The crosshairs are centered on a ventilation shaft. The shaft is on the roof of The Republican Guard Palace in downtown Baghdad across the Tigris River.

Saddam Hussein is inside, seven floors below, three floors below ground level, attending a crisis meeting. Mike's co-worker Pete (also an Ironman finisher, Lake Placid, 2000) keys some information into a small laptop computer and hits "burst transmit". The DMDG (Digital Message Device Group) uplinks data to another of Mike's co-workers (this time a man he's never met, but they both work for their Uncle, "Sam") and a fellow athlete, at 21'500 feet above Iraq 15 miles from downtown Baghdad. This man's office is the cockpit of an F-117 stealth fighter. When Mike and Pete's signal is received the man in the airplane leaves his orbit outside Baghdad, turns left, and heads downtown. Mike has 40 seconds to complete his work for tonight, then he can go for a run.

Mike squeezes the trigger of his LF25 and a dot appears on the ventilator shaft five city blocks and across the river away from him and his co-workers. Mike speaks softly into his microphone; "Target illuminated. Danger close. Danger Close. Danger close. Over." Seconds later two GBU-24B two thousand pound laser guided, hardened case, delayed fuse "bunker buster" bombs fall free from the F-117. The bombs enter "the funnel" and begin finding their way to the tiny dot projected by Mike's LF25. They glide approximately three miles across the ground and fall four miles on the way to the spot marked by Mike and his friends. When they reach the ventilator shaft marked by Mike and his friends the two bunker busters enter the roof in a puff of dust and debris. They plow through the first four floors of the building like a two-ton steel telephone pole traveling over 400 m.p.h., tossing desks, ceiling tiles, computers and chairs out the shattering windows. Then they hit the six-foot thick reinforced concrete roof of the bunker. They burrow four more feet and detonate.

The shock wave is transparent but reverberates through the ground to the river where a Doppler wave appears on the surface of the Tigris. When the seismic shock reaches the building Mike is on he levitates an inch off the roof from the concussion. Then the sound hits. The two explosions are like a simultaneous crack of thunder as the building's walls seem to swell momentarily, then burst apart on an expanding fireball that slowly, eerily, boils above Baghdad blasting rotating shadows as the fire climbs into the night. Debris begins to rain; structural steel, chunks of concrete, shards of glass, flaming fabrics and papers. On the tail of the two laser guided bombs a procession of BGM-109G/TLAM Block IV Enhanced Tomahawks begin their terminal plunge. The laser-guided bombs performed the incision, the GPS and computer guided TLAM Tomahawks complete the operation. In rapid-fire succession the missiles find their mark and riddle the Palace with massive explosions, finishing the job. The earth heaves in a final death convulsion.

The shock wave is transparent but reverberates through the ground to the river where a Doppler wave appears on the surface of the Tigris. When the seismic shock reaches the building Mike is on he levitates an inch off the roof from the concussion. Then the sound hits. The two explosions are like a simultaneous crack of thunder as the building's walls seem to swell momentarily, then burst apart on an expanding fireball that slowly, eerily, boils above Baghdad blasting rotating shadows as the fire climbs into the night. Debris begins to rain; structural steel, chunks of concrete, shards of glass, flaming fabrics and papers. On the tail of the two laser guided bombs a procession of BGM-109G/TLAM Block IV Enhanced Tomahawks begin their terminal plunge. The laser-guided bombs performed the incision, the GPS and computer guided TLAM Tomahawks complete the operation. In rapid-fire succession the missiles find their mark and riddle the Palace with massive explosions, finishing the job. The earth heaves in a final death convulsion.

Mike's job is done for tonight. Now all he has to do is get home. Mike and his friends drive an old Mercedes through the streets of Baghdad as the sirens start. They take Jamia to Al Kut, cross Al Kut and go right (South) on the Expressway out of town. An unsuspecting remote CNN camera mounted on the balcony of the Al Rashid Hotel picks up their vehicle headed out of town. Viewers at home wonder what a car is doing on the street during the beginning of a war. They don't know it is packed with five members of the U.S. Army's SFOD-D, Special Forces Operational Detachment - Delta. Delta Force.

Six miles out of town they park their Mercedes on the shoulder, pull their gear out of the trunk and begin to run into the desert night. The moon is nearly full. Instinctively they fan out, on line, in a "lazy 'W' ". They run five miles at a brisk pace, good training for this evening, especially with 27 lb. packs on their back. Behind them there is fire on the horizon. Mike and his fellow athletes have a meeting to catch, and they can't be late. Twenty seven miles out a huge gray 92 foot long insect hurtles 40 feet above the desert at 140 m.p.h. The MH-53J Pave Low III is piloted by another athlete, also a triathlete, named Jim, from Fort Campbell, Kentucky. He is flying to meet Mike. After running five miles into the desert Mike uses his GPS to confirm his position. He is in the right place at the right time. He removes an infra-red strobe light from his pack and pushes the red button on the bottom of it. It blinks invisibly in the dark. He and his friends form a wide 360 degree circle while waiting for their ride home. Two miles out Jim in the Pave Low sees Mike's strobe through his night vision goggles. He gently moves the control stick and pulls back on the collective to line up on Mike's infra-red strobe. Mike's ride home is here.

The big Pave Low helicopter flares for landing over the desert and quickly touches down in a swirling tempest of dust. Mike and his friends run up the ramp after their identity is confirmed. Mike counts them up the ramp of the helicopter over the scream of the engines. When he shows the crew chief five fingers the helicopter lifts off and the ramp comes up. The dark gray Pave Low spins in its own length and picks up speed going back the way it came, changing course slightly to avoid detection.

The men and women in our armed forces, especially Special Operations, are often well trained, gifted athletes. All of them,

including Mike, would rather be sleeping the night away in anticipation of a long training ride rather than laying on a damp

roof in an unfriendly neighborhood guiding bombs to their mark or doing other things we'll never hear about.

Regardless of your opinions about the war, the sacrifices these people are making and the risks they are taking are extraordinary. They believe they are making them on our behalf. Their skills, daring and accomplishments almost always go unspoken. They are truly Elite Athletes.

The Average Age of the Military

Man is 19 Years

He is a short haired, tight-muscled kid who, under normal circumstances is

considered by society as half man, half boy. Not yet dry behind the ears, not old enough to buy a beer, but old enough to die for his country.

He never really cared much for work and he would rather wax his own car than wash his father's; but he has never collected unemployment either.

He's a recent High School graduate; he was probably an average student, pursued some form of sport activities, drives a ten year old jalopy, and has

a steady girlfriend that either broke up with him when he left, or swears to be waiting when he returns from half a world away.

He listens to rock and roll or hip-hop or rap or jazz or swing and 155mm Howitzers.

He is 10 or 15 pounds lighter now than when he was at home because he is working or fighting from before dawn to well after dusk.

He has trouble spelling, thus letter writing is a pain for him, but he can field strip a rifle in 30 seconds and reassemble it in less time in the

dark.

He can recite to you the nomenclature of a machine gun or grenade launcher and use either one effectively if he must.

He digs foxholes and latrines and can apply first aid like a professional.

He can march until he is told to stop or stop until he is told to march.

He can march until he is told to stop or stop until he is told to march.

He obeys orders instantly and without hesitation, but he is not without spirit or individual dignity.

He is self-sufficient. He has two sets of fatigues: he washes one and wears the other.

He keeps his canteens full and his feet dry.

He sometimes forgets to brush his teeth, but never to clean his rifle.

He can cook his own meals, mend his own clothes, and fix his own hurts.

If you're thirsty, he'll share his water with you; if you are hungry, his food.

He'll even split his ammunition with you in the midst of battle when you run low.

He has learned to use his hands like weapons and weapons like they were his hands. He can save your life - or take it, because that is his job.

He will often do twice the work of a civilian, draw half the pay and still find ironic humor in it all. He has seen more suffering and death then he

should have in his short lifetime.

He has stood atop mountains of dead bodies, and helped to create them.

He has wept in public and in private, for friends who have fallen in combat and is unashamed.

He feels every note of the National Anthem vibrate through his body while rigid attention, while tempering the burning desire to 'square-away' those

around him who haven't bothered to stand, remove their hat, or even stop talking. In an odd twist, day in and day out, far from home, he defends

their right to be disrespectful.

Just as did his Father, Grandfather, and Great-grandfather, he is paying the price for our freedom.

Beardless or not, he is not a boy.

He is the American Fighting Man that has kept this country free for over 200 years.

He has asked nothing in return, except our friendship and understanding.

Remember him, always, for he has earned our respect and admiration with his blood.

1st Hand account FW: INFO: AH-1Ws Iraq Battle Account 30 Mar 03

Sent: 3/30/03 7:34 PM

Subject: SITREP

Sir,

Thought that you might like to hear how the Scarface det is doing out here. We've been heavily involved in the fighting. I'll stick to mostly reporting on my division's actions, as those are the ones that I know the best. My division is made up of the following pers:

Lead: BT had been flying the first 8 days with Maj Bussel, a MAWTS guy from group, but now he has been pulled back to plan for further operations north. His co-pilot will probably be Count -2:

Maj Johnson and sometimes Count, although Jo-Jo Laughlin has been filling in too.

-3 Weasel and IKE

-4 Myself and Gash

We flew the first night of the war, striking several Iraqi border posts prior to the ground guys crossing the berm. Recovered at the FARP and slept the night. Did about 8 hours of missions the next day, mostly shooting unmanned ZU-23's and ZPU-4's in the Rumaylah oil fields. Did find some troops who wanted to fight and took them out with rockets and 20mm. Next day we went out around 1600, and flew for 18.9 of the next 21 hours. The night was

uneventful, just getting shuttled from FAC to FAC looking for work. Was actually very boring as we found nothing to shoot at. Around hour 13 of our mission, we got tasked with an immediate mission up at An Nasiriyah. Our column had just been ambushed and were in heavy contact with troops cut off. We were the first rotors on station. We killed 5 ZU-23's, 3 T-55's, and approx 30-40 troops. They were fighting back. I took two rounds in the bottom of my A/C from a squad that had hidden in a schoolyard of women and children. Maj Bussel saw them jump out as I passed and got me to break away from the threat. I never saw them. The next day we went out again.

We flew the first night of the war, striking several Iraqi border posts prior to the ground guys crossing the berm. Recovered at the FARP and slept the night. Did about 8 hours of missions the next day, mostly shooting unmanned ZU-23's and ZPU-4's in the Rumaylah oil fields. Did find some troops who wanted to fight and took them out with rockets and 20mm. Next day we went out around 1600, and flew for 18.9 of the next 21 hours. The night was

uneventful, just getting shuttled from FAC to FAC looking for work. Was actually very boring as we found nothing to shoot at. Around hour 13 of our mission, we got tasked with an immediate mission up at An Nasiriyah. Our column had just been ambushed and were in heavy contact with troops cut off. We were the first rotors on station. We killed 5 ZU-23's, 3 T-55's, and approx 30-40 troops. They were fighting back. I took two rounds in the bottom of my A/C from a squad that had hidden in a schoolyard of women and children. Maj Bussel saw them jump out as I passed and got me to break away from the threat. I never saw them. The next day we went out again.

After several uneventful hours, small firefights and us shooting up some buildings that had been sniping at friendlies, we found a town with technicals, killing several with ZU-23's in the back and some with heavy MG's. We got caught north of a bad sandstorm and had to stay out for 3 days. We flew CAS missions in vis down to 1/2 mile before determining that we were in more danger of running into each other and wires than enemy fire.

The ground troops were not taking any fire, so we went to the FARP and shut down. Following a very wet and cold night, we got up again and went back out. This time we pushed a little north of the friendlies to recce a town. We found a platoon + that was setting up an ambush. JoJo killed a technical with a TOW, and I killed a ZU-23 with a HF. The ground troops had holes and trenches and opened up on us too. BT raked a trenchline with 20mm, killing a bunch. Maj Bussel shot several with HE rockets as they tried to run. IKE and Weasel fired a pod of nails into a squad, killing all but one. Gash fired a flechette that armed about an arms length from a runner, deflating him with the nails. Our 20's have been taking a beating. I have yet to have one that works. It really sucks to have troops in your sights and not have a weapon to engage them with. Our division has the day and night off, truly needed. We have flown 57 hours in 8 days, and were quite tired. In other news, Beaver (an old Scarface guy from 303- Maj Gilliland) shot a guy in his truck, killing him with his M-16 while Doogie (another Scarface UH driver) flew. If you've been watching FOX news, Ollie North was flying in the back of Flowbee and Chief's huey when they got in contact. He taped the whole engagement and I think that it has been showing on the news. What happened was this. Cpl Homan, one of the gunners, saw a squad break and run out of a building. One tripped and his weapon went skidding across the deck. That cue'd his eyes and he opened up. Flowbee put a rocket through the window of the building and more came out. Homan and Northcott mowed them down.

That's about it from here. We've been working hard, and still looking for more work. Maj Burton says hello. He flew with us for the first couple days, but is now back at group I believe.

V/R

ShoeShine

An Army Like No Other

By Jim Lacey, a Time magazine correspondent

Mr. Lacey was embedded with the 101st Airborne Division.

Since returning from Iraq a short time ago I have been answering a lot of questions about the war from friends, family, and strangers. When they ask me how it was over there I find myself glossing over the fighting, the heat, the sandstorms, and the flies (these last could have taught the Iraqi

army a thing or two about staying power). Instead, I talk about the soldiers I met, and how they reflected the best of America. A lot of people are going to tell the story of how this war was fought; I would rather say something about the men who won the war.

War came early for the 1st Brigade of the 101st Airborne when an otherwise quiet night in the Kuwaiti desert was shattered by thunderous close-quarters grenade blasts. Sgt. Hasan Akbar, a U.S. soldier, had thrown grenades into an officers' tent, killing two and wounding a dozen others. Adding to the immediate confusion was the piercing scream of SCUD alarms, which kicked in the second Akbar's grenade exploded. For a moment, it was a scene of near panic and total chaos.

War came early for the 1st Brigade of the 101st Airborne when an otherwise quiet night in the Kuwaiti desert was shattered by thunderous close-quarters grenade blasts. Sgt. Hasan Akbar, a U.S. soldier, had thrown grenades into an officers' tent, killing two and wounding a dozen others. Adding to the immediate confusion was the piercing scream of SCUD alarms, which kicked in the second Akbar's grenade exploded. For a moment, it was a scene of near panic and total chaos.

Just minutes after the explosions, a perimeter was established around the area of the attack, medics were treating the wounded, and calls for evacuation vehicles and helicopters were already being sent out. Remarkably, the very people who should have been organizing all of this were the ones lying on the stretchers, seriously wounded. It fell to junior officers and untested sergeants to take charge and lead. Without hesitation everyone stepped up and unfalteringly did just that. I stood in amazement as two captains (Townlee Hendrick and Tony Jones) directed the evacuation of

the wounded, established a hasty defense, and helped to organize a search for the culprit. They did all this despite bleeding heavily from their wounds. For over six hours, these two men ran things while refusing to be evacuated until they were sure all of the men in their command were safe.

Two days later Capt. Jones left the hospital and hitchhiked back to the unit: he had heard a rumor that it was about to move into Iraq and he wanted to be there. As Jones - dressed only in boots, a hospital gown, and a flak vest - limped toward headquarters, Col. Hodges, the 1st Brigade's commander, announced, "I see that Captain Jones has returned to us in full martial splendor." The colonel later said that he was tempted to send Jones to the unit surgeon for further evaluation, but that he didn't feel he had the right to tell another man not to fight: Hodges himself had elected to leave two grenade fragments in his arm so that he could return to his command as quickly as possible.

The war had not even begun and already I was aware that I had fallen in with a special breed of men. Over the next four weeks, nothing I saw would alter this impression. A military historian once told me that soldiers could forgive their officers any fault save cowardice. After the grenade attack I knew these men were not cowards, but I had yet to learn that the brigade's leaders had made a cult of bravery. A few examples will suffice.

While out on what he called "battlefield circulation," Col. Hodges was surveying suspected enemy positions with one of his battalion commanders (Lt. Col. Chris Hughes) when a soldier yelled "Incoming" to alert everyone that mortar shells were headed our way. A few soldiers moved closer to a wall, but Hodges and Hughes never budged and only briefly glanced up when the rounds hit a few hundred yards away. As Hodges completed his review and prepared to leave, another young soldier asked him when they would get to kill whoever was firing the mortar. Hodges smiled and said, "Don't be in a hurry to kill him. They might replace that guy with someone who can shoot."

The next day, a convoy that Col. Hodges was traveling in was ambushed by several Iraqi paramilitary soldiers. A ferocious firefight ensued, but Hodges never left the side of his vehicle. Puffing on a cigar as he directed the action, Hodges remained constantly exposed to fire. When two Kiowa helicopters swooped in to pulverize the enemy strongpoint with rocket fire, he turned to some journalists watching the action and quipped, "That's your tax dollars at work."

Bravery inspires men, but brains and quick thinking win wars. In one particularly tense moment a company of U.S. soldiers was preparing to guard the Mosque of Ali - one of the most sacred Muslim sites - when agitators in what had been a friendly crowd started shouting that they were going to storm the mosque. In an instant, the Iraqis began to chant and a riot seemed imminent. A couple of nervous soldiers slid their weapons into fire mode, and I thought we were only moments away from a slaughter. These soldiers had just fought an all-night battle. They were exhausted, tense, and prepared to crush any riot with violence of their own. But they were also professionals, and so, when their battalion commander, Chris Hughes, ordered them to take a knee, point their weapons to the ground, and start smiling, that is exactly what they did. Calm returned. By placing his men in the most non-threatening posture possible, Hughes had sapped the crowd of its aggression. Quick thinking and iron discipline had reversed an ugly situation and averted disaster.

Since then, I have often wondered how we created an army of men who could fight with ruthless savagery all night and then respond so easily to an order to "smile" while under impending threat. Historian Stephen Ambrose said of the American soldier: "When soldiers from any other army, even our allies, entered a town, the people hid in the cellars. When Americans came in, even into German towns, it meant smiles, chocolate bars and C-rations." Ours has always been an army like no other, because our soldiers reflect a society unlike any other. They are pitiless when confronted by armed enemy fighters and yet full of compassion for civilians and even defeated enemies.

American soldiers immediately began saving Iraqi lives at the conclusion of any fight. Medics later said that the Iraqi wounded they treated were astounded by our compassion. They expected they would be left to suffer or die. I witnessed Iraqi paramilitary troops using women and children as human shields, turning grade schools into fortresses, and defiling their own holy sites. Time and again, I saw Americans taking unnecessary risks to clear buildings without firing or using grenades, because it might injure civilians. I stood in awe as 19-year-olds refused to return enemy fire because it was coming from a mosque.

It was American soldiers who handed over food to hungry Iraqis, who gave their own medical supplies to Iraqi doctors, and who brought water to the thirsty. It was American soldiers who went door-to-door in a slum because a girl was rumored to have been injured in the fighting; when they found her,they called in a helicopter to take her to an Army hospital. It was American soldiers who wept when a three-year-old was carried out of the rubble where she had been killed by Iraqi mortar fire. It was American soldiers who cleaned up houses they had been fighting over and later occupied-they wanted the places to look at least somewhat tidy when the residents returned.

It was these same soldiers who stormed to Baghdad in only a couple of weeks, accepted the surrender of three Iraqi Army divisions, massacred any Republican Guard unit that stood and fought, and disposed of a dictator and a regime with ruthless efficiency. There is no other army - and there are no other soldiers - in the world capable of such merciless fighting and possessed of such compassion for their fellow man. No society except America could have produced them.

Before I end this I want to point out one other quality of the American soldier: his sense of justice. After a grueling fight, a company of infantrymen was resting and opening their first mail delivery of the war. One of the young soldiers had received a care package and was sharing the home-baked cookies with his friends. A photographer with a heavy French accent asked if he could have one. The soldier looked him over and said there would be no cookies for Frenchmen. The photographer then protested that he was half Italian. Without missing a beat, the soldier broke a cookie in half and gave it to him. It was a perfect moment and a perfect reflection of the American soldier.

Joke

A squad of American soldiers was patrolling along the Iraqi border. To their surprise, they found the badly mangled dead body of an Iraqi soldier in a ditch along side the road.

Nearby, they found a badly mangled American soldier in a ditch on the other side of the road, who was still barely alive. They ran to him, cradled his blood-covered head and asked him what had happened.

"Well," he whispered, "I was walking down this road, armed to the teeth. I came across this heavily armed Iraqi border guard. I looked him right in the eye and shouted, 'Saddam Hussein is an unprincipled, lying piece of dirt!'"

He looked me right in the eye and shouted back, "Bill Clinton, Tom Daschle, Ted Kennedy and most of your Democrats are unprincipled, lying pieces of dirt, too!"

"We were standing there shaking hands when a truck hit us."

Taps

We in the United States have all heard the haunting song, "Taps."

It's the song that gives us that lump in our throats and usually tears in our eyes.

But, do you know the story behind the song? If not, I think you will be interested to find out about

its humble beginnings. Reportedly, it all began in 1862 during the Civil War when Union Army

Captain Robert Ellicombe was with his men near Harrison's Landing in Virginia. The Confederate Army was on the other side of the narrow

strip of land. During the night, Captain Ellicombe heard the moans of a soldier who

lay severely wounded on the field. Not knowing if it was a Union or Confederate soldier, the

captain decided to risk his life and bring the stricken man back for medical attention.

Crawling on his stomach through the gunfire, the captain reached the stricken soldier and began pulling him toward his encampment.

When the captain finally reached his own lines, he discovered it was

actually a Confederate soldier, but the soldier was dead. The captain lit a lantern and suddenly caught his breath and went

numb with shock. In the dim light, he saw the face of the soldier. It was his own son.

The boy had been studying music in the South when the war broke out. Without telling his father, the boy enlisted in the Confederate

Army. The following morning, heartbroken, the father asked permission of his superiors to give his son a full military burial, despite his

enemy status. His request was only partially granted.

When the captain finally reached his own lines, he discovered it was

actually a Confederate soldier, but the soldier was dead. The captain lit a lantern and suddenly caught his breath and went

numb with shock. In the dim light, he saw the face of the soldier. It was his own son.

The boy had been studying music in the South when the war broke out. Without telling his father, the boy enlisted in the Confederate

Army. The following morning, heartbroken, the father asked permission of his superiors to give his son a full military burial, despite his

enemy status. His request was only partially granted.

The Captain had asked if he could have a group of Army band members

play a funeral dirge for his son at the funeral. The request was turned down since the soldier was a Confederate.

But out of respect for the father, they did say they could give him only one musician.

The captain chose a bugler. He asked the bugler to play a series of musical notes he had found

on a piece of paper in the pocket of the dead youth's uniform. This wish was granted.

The haunting melody, we now know as "Taps" ... used at military funerals was born. The words are:

Day is done

Gone the sun

From the lakes

From the hills

From the sky

All is well

Safely rest

God is thy

Fading light

Dims the sight

And a star

Gems the sky

Gleaming bright

From afar

Drawing thy

Falls the night

Thanks and praise

For our days

Neath the sun

Neath the stars

Neath the sky

As we go

This we know

God is thyn

PLEASE REMEMBER THOSE LOST AND HARMED WHILE SERVING OUR COUNTRY.